This seems like a good point in time to note: I’ve resisted getting involved with the Martirano materials/SalMar (or an opportunity came and went in the form of that dance show), seeing as how I have enough trouble focusing on my own creative impulses given the texture of life here and my states of mind. It is true, certainly, that in the past composers and musicians in general learned from each other by studying each others work. In the old days, this involved copying scores, playing scores through at sight on keyboards, reducing scores at sight, and, of course, listening to performances. In more recent days, we can look at scores aplenty via the internet, and for more than a century, we’ve been able to listen to recorded performances. So it’s not unheard of for a composer to soak in another persons output. So for me, the upcoming SalMar blast, which is itself part of still ANOTHER composers doings, ie., David Rosenboom of Cal Arts, is just another prod, another impetus to dance with Sal. And so, having been fooling with it, messing with it, I’ve gotten it on me. Again.

I finally fished out that hard drive that I got from John Martirano, Sal’s surviving son, at the time I had finished digitizing selected reels of tape from the body of materials that went to the Sousa Archive in 2010, and ’11. I got curious because Greg Danner relies on a print out of a PDF in a nice notebook that shows him the patching, the board layouts, and all sorts of technical data that are crucial to maintenance of the SalMar Construction.

Also on the hard drive, though, are all sorts of other materials. A man’s creative life, in essence. I can stick to just stuff that relates to the SalMar, and still have way too much to take in. But that does not mean I can’t come up with ways to take some of it in. So, for starters, I tried to find a reasonable beginning by listening to “J35” — ‘early machine,’ (with a disorienting blast of jazz duo in hard bop mode at the head of the spool), while simultaneously reading the SalMar_04_003 document, which (with John Martirano acting as Köchel for his father’s papers) is the catalog number for :

Progress Report #1

An Electronic Music Instrument Which Combines Composing Process with Performance in Real Time

Salvatore Martirano

It’s a typescript, but in Sal’s handwriting, he notes the date; April, 1971.

This is a stab at several things at once: it is a history of Sal’s work on ‘the machine.’ It is a description of what it is and what it might become. It is a listing of the many collaborators involved up to the point in time the paper was crafted, and it is a justification and request for support — the indelible, immoveable features of an academic career. He includes a review of an early performance of the MarVil Construction (early machine; early name) in the New York Times, photographs, block diagrams, and a list of references.

Taken in together, these documents are a good grounding in the lore of the SalMar Construction. I’m a bit late getting around to these. Better late than never.

It took less time to listen to J35 than it took to read the Progress Report. And the progress report has lots of pictures, diagrams, and charts. Then, I cued up Underworld, a Martirano composition for chamber orchestra and tape referred to in the PR. I own a copy of the Heliodor recording Electronic Music from the University of Illinois, so this involved spinning vinyl on a turntable. While doing this, I commenced the reading of

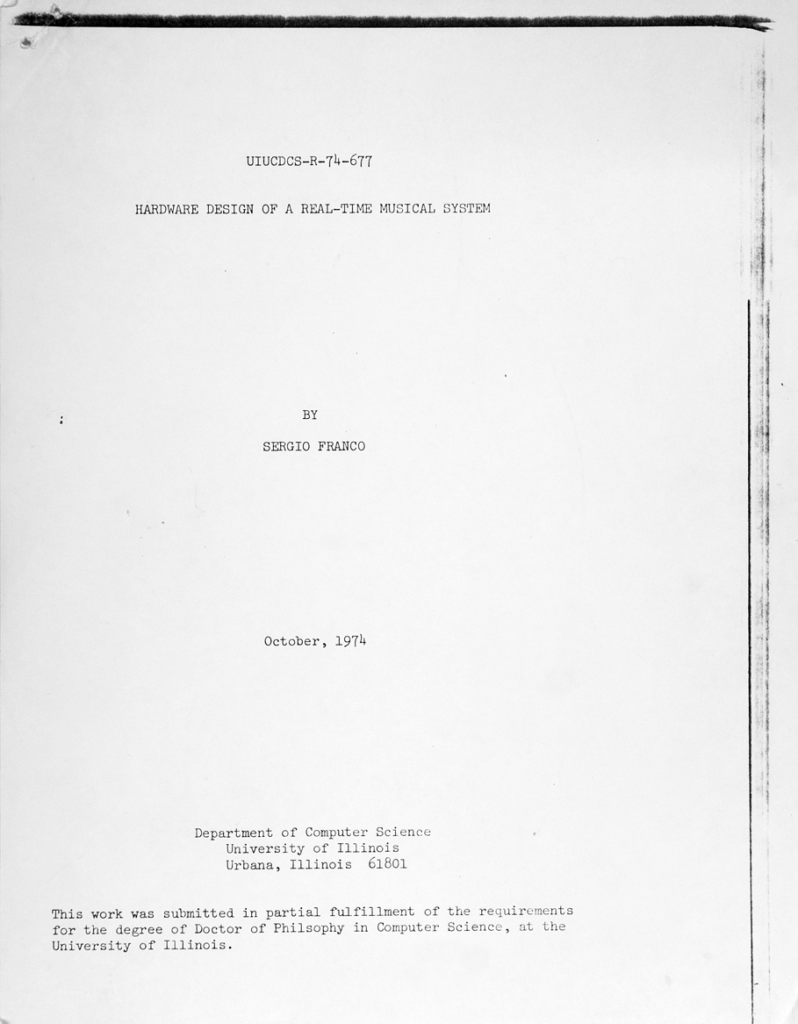

… which got me to thinking (again) about academia, in which teams of people work together on a project and somebody writes it up for credit. Franco’s thesis is the clearest representation of the methods and motivations employed by the SalMar construction there is. It has a marvelous diagram at the outset that makes clear the structure of the instrument:

How’s that for concise?

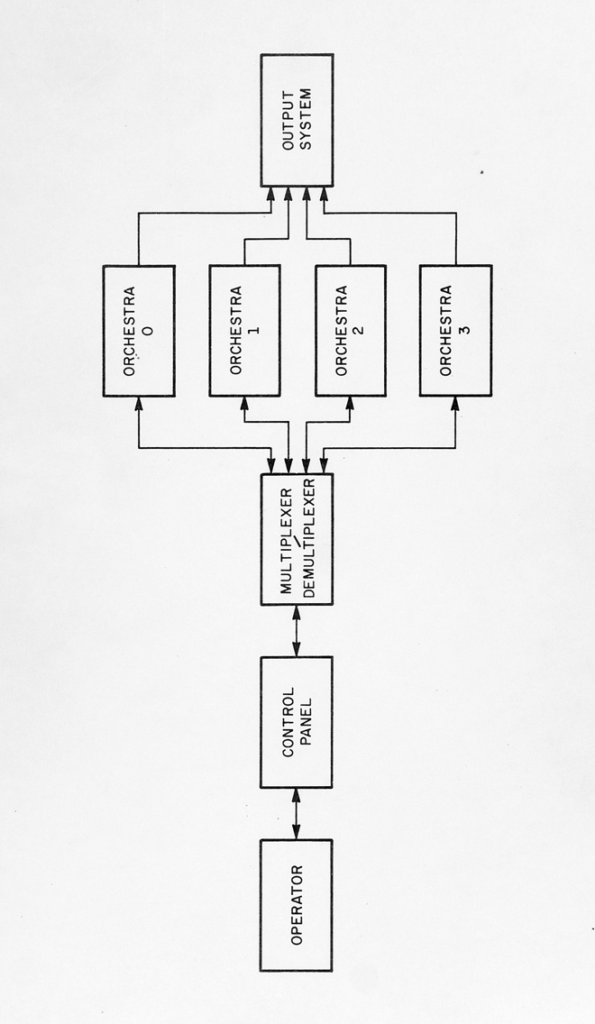

And the relationship of the clocks to one another:

… for which, in a footnote, Martirano gets specifically credited. Of course, Sal’s name is given to the instrument overall, and at a certain point, it became his baby. It lived in his house, having arrived at the Sousa Archive/The Center for American Music in the Harding Band Building from there.

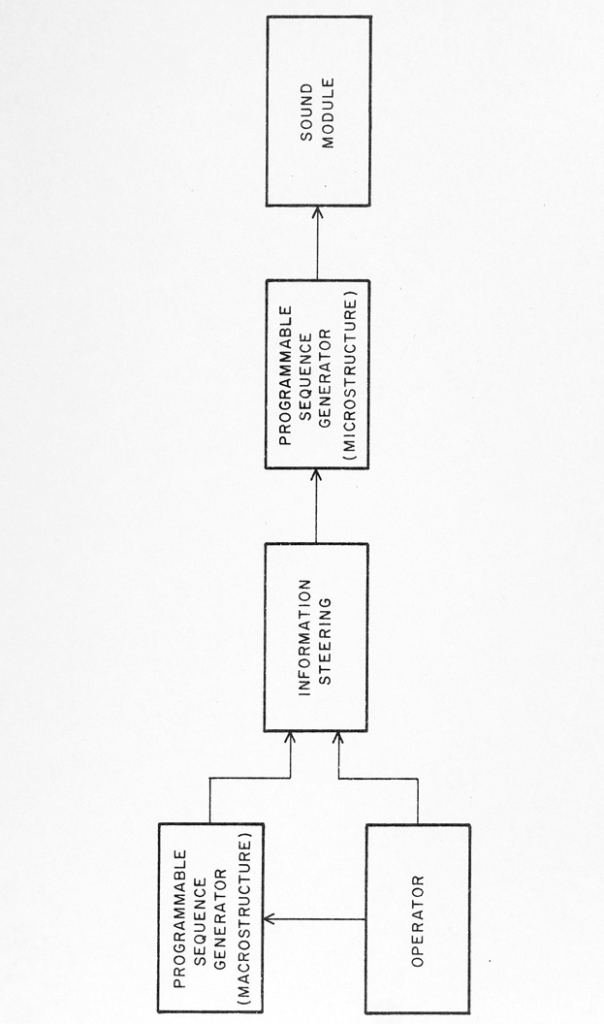

The text of the thesis makes clear the nature of the machine: it makes constant micro decisions, while the operator decides what level of macro decision making falls under automatic or manual control. The decision making is independent of the usual parametric analysis. Envelopes, the containers of sound, are not pitch specific. Pitches are divisions of the octave, and the number of divisions is selectable in this context of auto/manual control. Every parameter is selectable in this way: the distinction is essentially do I want to be involved? If so, how much? How much do I want the logic circuits to do for me? And, I presume, one can hear Sal chuckling at this. For who? Hoo hoo hoo!

Much space is devoted, both in the PR document and in Franco’s thesis, to the sound distribution system. This system is not present in the current installation at the Harding Band Building on the University of Illinois campus. One can understand why this is: there is no room for it in the small museum space that is the Center for American Music. Not only are the 24 bubble-backed poly-planar speakers not present, but the 24 voltage controlled amplifiers that drove them are also missing. The archive apparently retained some examples. I ended up with a few spare automobile-type speakers and one of the poly-planars. I have perhaps a set of the heavy, formica baffles, in cardboard boxes, with and without speakers, also. There was a shift apparently from the auto speakers with cones to the poly-planars, which made the baffles redundant, but still required the bubble-backs. It is a bit of a shame that the instrument is in a museum, in the sense that, as with any musical instrument, its purpose is performance. It joins Paderewski’s piano, and the Harry Partch instruments in this fate, though I think the Partch instruments are maintained and played. It would be my hope that there might be a way to bring at least the concepts of the SalMar to fruition in software, but I don’t see a future for a 24 speaker array. As it is, the instrument is used in four-channel studio mode, and there is an unused area of the control panel which represents the sound distribution system.

As the Franco thesis comes to a close, the discussion turns away from detailed technical descriptions of the sound-producing components and towards the operator-machine interface. This is discussed as real-time control, in which processes that occur less than once per second (1 Hz) is deemed too fast for human capability (arguable), and gets at the structure of the instrument in the crucial way: how does the user effectively interact with the SalMar? Another facet of the conceptual framework is the idea of micro and macro processes. Pitch and pitch sequencing, timbre, and envelope generation are largely treated as micro processes with macro implications. I have noted, with a certain amount of epiphanic shock, that envelopes are independent of pitch sequences. Franco notes that envelopes and the generation of envelopes are processes that are applicable systemically. This, to me, is a radical departure from every other synthesis concept, even now, nearly 50 years later. Or is it that I’m missing something? Always possible. We live in our poly-planar bubbles, baffled.

Coming up tomorrow (October 4th, 2022) is Rosenboom’s lecture on things SalMar at The School of Music Auditorium. I’ll be at Sousa, with Greg Danner, playing the SalMar four-hand style. In speaking with Greg last Friday, on the occasion of our final work session before the gig, I mentioned, again, the need for a ‘players manual.’ He said Sal was often asked for such a thing, but demurred, being of the opinion that the SalMar was one of his compositions, and only he needed to interface with it. He has passed, leaving behind the bewitching instrument and a few stray acolytes. Perhaps something can be brought forth from that circumstance.