Hear it on bandcamp!

Continuing the perusal of past work on magnetic tape…

I recall some of the ‘Mississippi Mud’ out of which emerged the idea to make a ballet out of Mark Twain’s sprawling novel. Let me attempt to detail, to the best of my recollection, how this came to happen.

It was a collaboration. Almost all work in theater is necessarily collaborative. The architects of this particular collaboration were me, a choreographer I’d met at Boston Conservatory named Randall Barron, and a choreographer and company director named Elizabeth Hard. Liz has died, but Randy’s very much still alive and well.

The Boston Conservatory gang I was part of, in 1976, was a collection of BCM dancers with a few folks that Randy had known from his life in the American West and Midwest. Born in Colorado, Randy spent time in Kansas City and Sioux City before coming to Boston. These were the contacts that were key to the enterprises we undertook as collaborators. But in 1976, Randy graduated from BCM and headed to New York City to make a go of it in the Big Apple. I was left behind to finish my final year. After graduating myself in 1977, I was more than a bit freaked out. What the heck was I going to do? I decided to go for a nice long hike. I took a bus to Pittsfield, Massachusetts. I got on the Appalachian Trail there, and hiked down to Pauling, New York. Along the way, I had an epiphany. I had decided to ask Randy what his plans were. I knew he was not going to stay in New York and starve while working at Capezios on Broadway. Did I get wind of the plan to head to Sioux City? I don’t remember. In any case, I was made welcome as a member of this adventure. I packed up my stuff, shipped some ahead to an unknown woman’s address in Kansas City, and I went.

A bunch of brainstorming had been going on about work we might undertake. Randy had a deep interest in the wisdom and culture of Native Americans. We exchanged notes about a ‘ballet’ called Spirit of the Waters. I have notes, drafts, and exchanged messages about this project, collected in a folder during one of my periodic siftings of paperwork, but there is no date on any scrap of this paper. We must have started this dialogue during the span between my visit to NYC, and my departure for the midwest. We did not all set out at once…

Randy and his dancer bride-to-be had gone ahead to scope it out and plan their wedding.

Spirit of the Waters did not get made, at least not by me. Instead, Randy and I collaborated on another idea of his, The Hunt of the Unicorn. ‘Unicorn,’ did get made. It deserves its own examination, since it is an interesting score. But the idea of a Huck Finn ballet must have occurred to me nearly simultaneously. We were, perhaps, kicking around ideas that had some sort of personal or midwestern relevance, clearly without having much of an idea what would in fact appeal to midwesterners in the late 1970s. And that, possibly, is why Spirit of the Waters did not get made. In Sioux City, Iowa, in the 1970s, the origin of the name, as a Francophone misnomer for an indigenous tribal people, was something of a sore point. The organization we joined, one that Randy had been involved with before he showed up at BCM, was The Siouxland Civic Dance Association. The term Siouxland softened the blow, the shudder of collective guilt and indignation that the “Indian Wars” had left as a residue. These subtleties were lost on me at the time. I was just coming to grips with how sprawling and individuated the United States is, and how peculiar each individual State is.

And Huckleberry Finn is also problematic for other, obvious, reasons. But it’s set in Missouri, on the Mississippi, and that’s, uh, out there somewhere, isn’t it?

So there we were in Sioux City. Randy, as newly minted artistic director, managed several things in addition to his more fundamental calling: he changed the name of the company to the Ballet Sioux. And when I say ‘ballet,’ I mean ‘dance theater.’ But that doesn’t roll off the tongue, does it?

He also finagled a Comprehensive Employment Training Act grant from the Feds so that my position as music director could be sustained.

By this time, I had already started composing for the ballet. It seems to me I began with the Prelude, but that’s not backed up by the recorded evidence. I may have composed, in the sense of written out, the On the Mississippi Rag before the Prelude. In any case, there’s a recording from 1978, while we all still lived in Sioux City proper on Pierce Street not too far from the band shell and Grandview Park. The recording is of Dan Moore sight reading the On the Mississipi Rag. The date on the box is March 18, 1978. It was very soon after this, as documented in my notes, that the SCDA board of directors voted to dismiss Mr. Barron as artistic director.

I holed up on the agribusiness acres out of town. I had moved to the East, into a 2nd floor apartment, not in, but near Moville. I was in a funny mood. The gig had dried up; my collaborator and friend, Mr. Barron, had headed for the nearest civilization down the Missouri river, KCMO. It was Summer, 1978, and I was still collecting money monthly from the CETA grant. I had opted to stay, shacking up in the corn fields with my girlfriend, whose life I was making miserable with my black mood. I might have kicked back and enjoyed the situation, but I was too freaked out. The one joy I managed to take was a daily drive to a swimming hole. The woman I was shacked up with, whose name was Kari, had an automobile. It was a yellow Renault 5, with black stripes. I also drove the car to a library. I decided to actually read some Twain. Seemed like good lit to tackle under the circumstances. The library had Huckleberry Finn and the Paine biography. I read them both. When the time came to compose the collection of vignettes for the Jack Straws performance, this reading would give my work the shape it needed to get the ideas across in ragtime. I dawdled, though. There were other irons in the fire.

I recall jamming on and writing down the Prelude on Pierce Street. At that time, the process was a bit more laborious than it has over the years become. I’d sit down at the piano and improvise until an idea jelled. By ‘jelled’ I mean that I was able to repeat what I had improvised. This distinguished it from ‘jamming.’ In my mind, these days, ‘jamming’ is making music with the fingers, minimal mind or memory, happen what may. It’s a useful activity. The more the ‘mind’ is out of the process, the closer to ‘the muse’ the result. But for repeatability, the mind, particularly the memory must be involved. As my skill at sight reading has improved, intimately connected with technical attainment, the ability to memorize has diminished. In 1978, I was a poor reader, but my memory was much better. I have heard some speak of muscle memory. It is generally defined across various websites as, “the ability to reproduce a particular movement without conscious thought, acquired as a result of frequent repetition of that movement.” There’s certainly an element of that in the experience I am recalling. In order to hold in memory long enough to then grab a pencil (never used a pen!) and jot down what I had played, I had to have played it over and over, until it became repeatable. I remember doing this at Pierce Street, working on the Prelude.

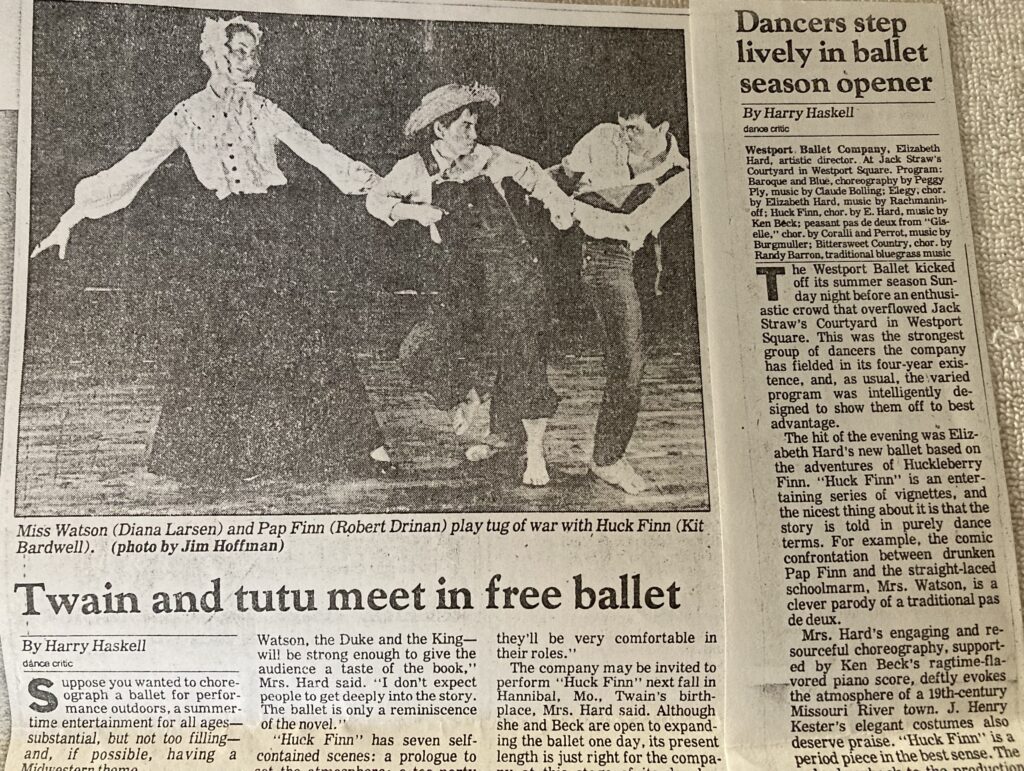

But it was the On the Mississippi Rag that Dan read. There was a score for that one in March of 1978. The manuscript is actually dated 1977!

Above, snapshots of the pencil manuscripts, page 1 of ‘Mississippi’ and the Prelude. The inspiration for the Prelude was something I read somewhere about the flow of the river. It was before the age of the internet, obviously. The number I had encountered was three. Three miles per hour… Now, I can google it and get:

“At the headwaters of the Mississippi, the average surface speed of the water is about 1.2 miles per hour – roughly one-half as fast as people walk. At New Orleans the river flows at about three miles per hour. But the speed changes as water levels rise or fall and where the river widens, narrows, becomes more shallow or some combination of these factors. It takes about three months for water that leaves Lake Itasca, the river’s source, to reach the Gulf of Mexico.”

But a slow walk is where I started my thinking about the flow of the Mississippi. Now I think I played the Prelude a bit too fast in the early recordings.

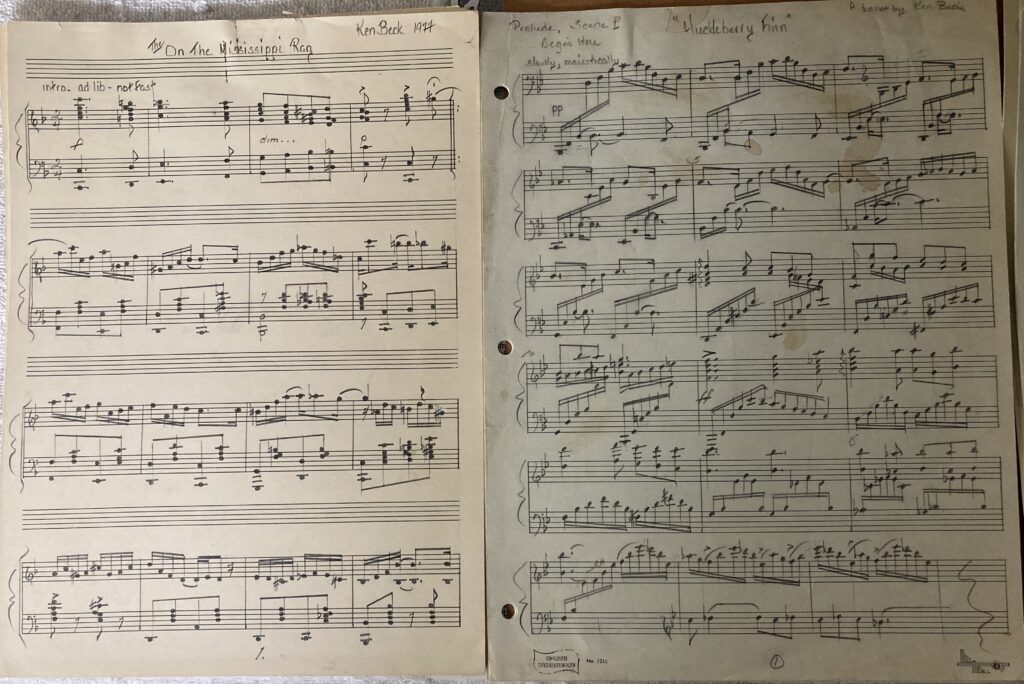

As with musicology and music manuscript forensics in general, a certain amount of dating information can be gleaned from paper types. The same paper type is used for the Prelude as Huck’s Rag. They were both composed at the house on Pierce Street in Sioux City. 1978. And after that, as noted above, disruption, relocation, and The Hunt of the Unicorn intervened.

Ragtime was in the air again in the 1970s. My friends and colleagues were on top if this; we collectively had heard and had copies of the recording by Rifkin and Gunther Schuller’s recording of The Red Back Book. In 1973, The Sting came out with, Redford and Newman. Dan Moore was playing Eubie Blake’s Charleston Rag, and various Lamb pieces, including American Beauty. Dan may well have been reading Lamb and not remembering it; but I’m sure the Charleston Rag sunk in a bit more, though perhaps not quite as much as Art Tatum’s Aunt Hagar’s Blues as it appeared transcribed in one of the John Mehegan books. I was learning constantly, by osmosis, driven home by intimidation.

Sousa was another component of the models for the Huck Finn pieces. So were the Mendelssohn Songs Without Words (Lieder Ohne Worte). My Prelude to Huck Finn is a ‘song without words.’ It might also be a song without a melody.

Composing the pieces began in earnest once I’d gotten established in Kansas City and I was working at the Westport Ballet. I really don’t recall meeting Elizabeth Hard for the first time. I remember instead beating the pavement for a gig in the beginning. I had fled the flat near Moville, with Kari. We moved into an apartment on Rockhill Road, near the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and the Kansas City Art Institute, and not too far from Old Westport, Brush Creek, and Country Club Plaza. Location, location, location. Not very many weeks went by before my friends, mentors, and collaborators got me in a room and had a ‘chat.’ Kari was fed up, wanted me to move out, and that was that. I was offered a space in ‘Chip’ Campfields apartment at 301 West 43rd Street. It was an offer I could not, and did not refuse. Meanwhile, I’d hiked way out Troost to the UMKC Dance Department and gotten hired as an accompanist. I also got a ‘straight job,’ but that’s another story for the general memoir (if there ever is one). In other words, I was back at it.

The Westport Ballet — the link is to Liz’s obit in the KC Star, which offers a capsule biography — was a relatively new operation. It was founded in 1974, taking the name of Old Westport, the neighborhood in midtown Kansas City where the school was established. Randy had already paved the way. I was happy to accompany class there, but there was initially no piano in the studio. All of these ‘growing pains’ resolved, and I got very quickly involved in the KCMO dance scene. The Westport Ballet put on a summer program at a restaurant called The Prospect of Westport, which adjoined a courtyard called Jack Straws. The link is to an article on the development of the area as an arts and entertainment hotspot. This paragraph sums up the relevant situation:

“A July 1977 article in The Star said Westport was known as an open-air strolling, drinking and dining area. It noted that there seemed to be a well-worn path from Kelly’s to the Harris House (then at 4057 Pennsylvania with an open-air deck on the roof) to Jack Straws Courtyard and Blayney’s and then down the alley to the Happy Buzzard where “de rigueur attire was a striped rugby shirt.” All had outdoor decks that would fill up during pleasant weather. Part of the courtyard behind the Prospect became a stage for free evening performances of the Westport Ballet.”

This was the setting for the premier performance of Huckleberry Finn: The Ballet.

Of course, once there was an opportunity to present the piece, a choreographer willing to tackle it, and a company to dance it, all that remained was to write the rest of it and record it. Right at the outset, I opted to make a recording and not to try playing live outdoors.

I recall taking a cassette recorder over to the UMKC Conservatory of Music practice rooms, down the street from 310 East 43rd street, just past the ‘toot,’ (our pejorative term for the KC Art Institute), and working on Jim’s Rag. In the beginning, I had no piano in Chip’s apartment. But eventually, with the rapidity that, in youth, seems like forever, I bought a Kurtzmann upright, restrung and re-pinned it, and made recordings on that.

The musical forensics, aka, the remains of the work on magnetic tape, yields a cassette tape made with a cheap portable cassette recorder, capturing me working on bits of Jim and Huck. Then, there are cassettes made on much better equipment, presumably in the apartment on the Kurtzmann. Finally, there are takes on reel to reel tape. These recordings complete the score, and were dubbed and played at Jack Straws.

The Widow Watson versus Old Man Finn was the 1st of the new pieces to be made for Jack Straws. I made the rest of the vignettes in short order: Jim’s Rag, (which was followed by On the Mississippi, repurposed for the ‘King and Duke,’ and a final ‘march past’ of all the characters in turn, with an opening and closing pair of strains. Listening now, the Jack Straws version of the piece has its delights. The playing — my playing — isn’t bad, better than I remember. The reel to reel master has multiple takes, with notes for editing. In the case of Widow Watson versus Old Man Finn, I made two takes and an edit piece. The first take is not terrible, and it’s complete. The second take is even better in general, but falls apart at the end, so I made an edit piece and helpfully left my future self notes on how to assemble a good, useable take. When digitizing, I digitized the entire spool, then followed my own advice and edited as instructed. In Sioux City, with some of that CETA money, I had purchased a Pioneer RT-701. I seem to recall hauling this heavy thing around to theaters, but it’s possible that the playback medium in the courtyard was cassette. I still had the Sony 355, so tape to tape copy was possible. But I don’t find any tape copy sub-masters of Huck. Cassette copies exist, including one from Randy with the Westport Ballet logo sticker on it. That one could very well be the copy played at the gigs. There are also no reel to reel masters of the Prelude and Huck’s Rag. Wither I have not discovered them yet, or I mastered to cassette and made performance copy from that, plus the reel to reel stuff as it got made. Considering this possibility now, this seems like a mixture of laziness and haste. I wasn’t thinking of the future; I was thinking of the gig. That’s show biz!

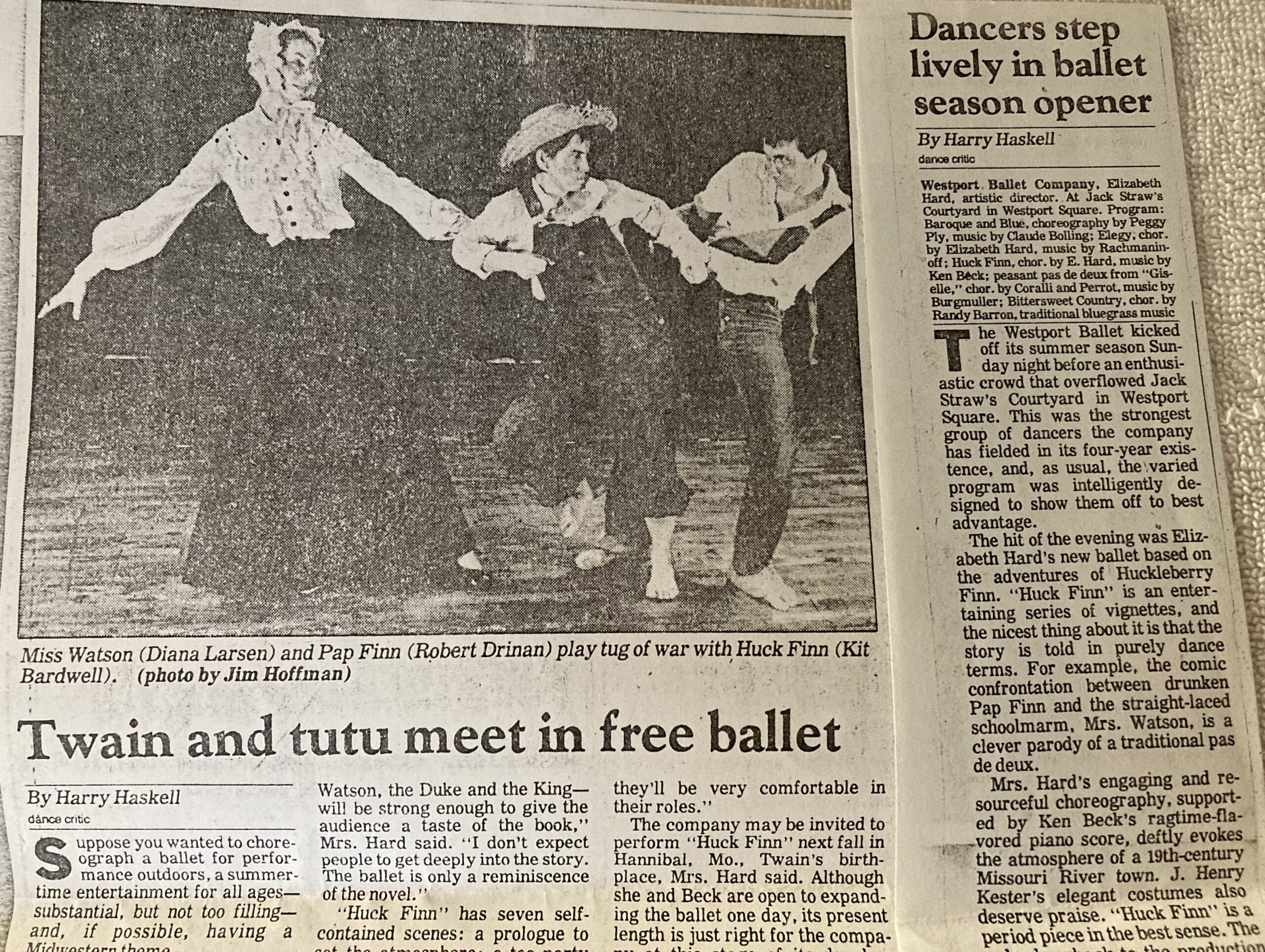

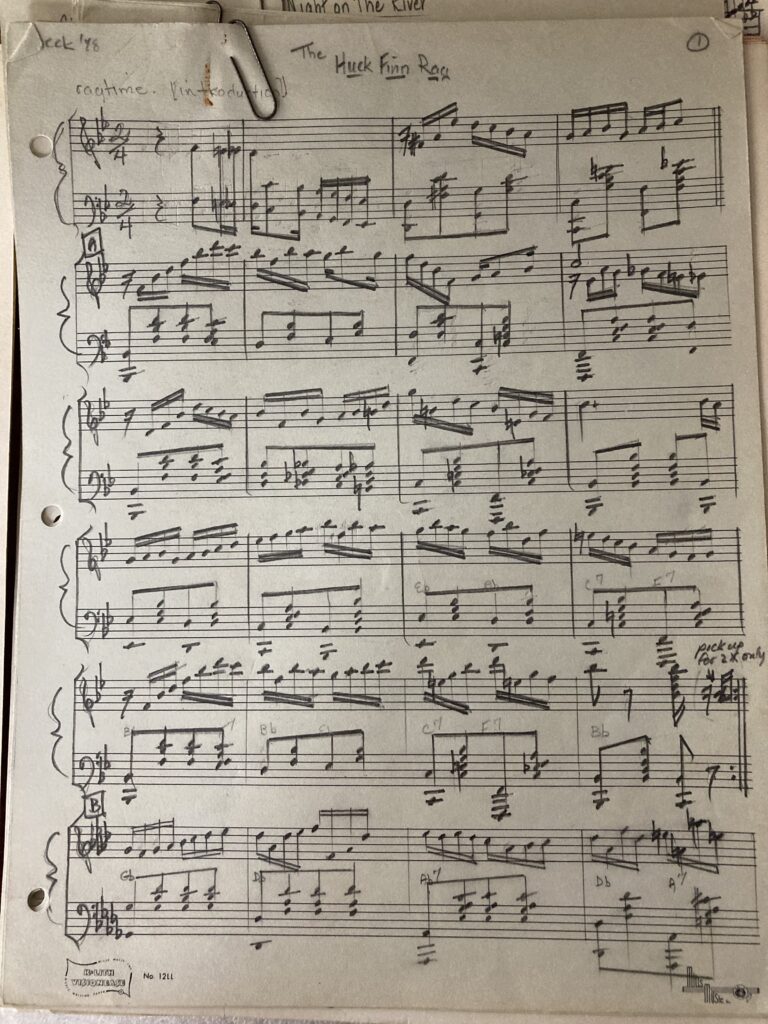

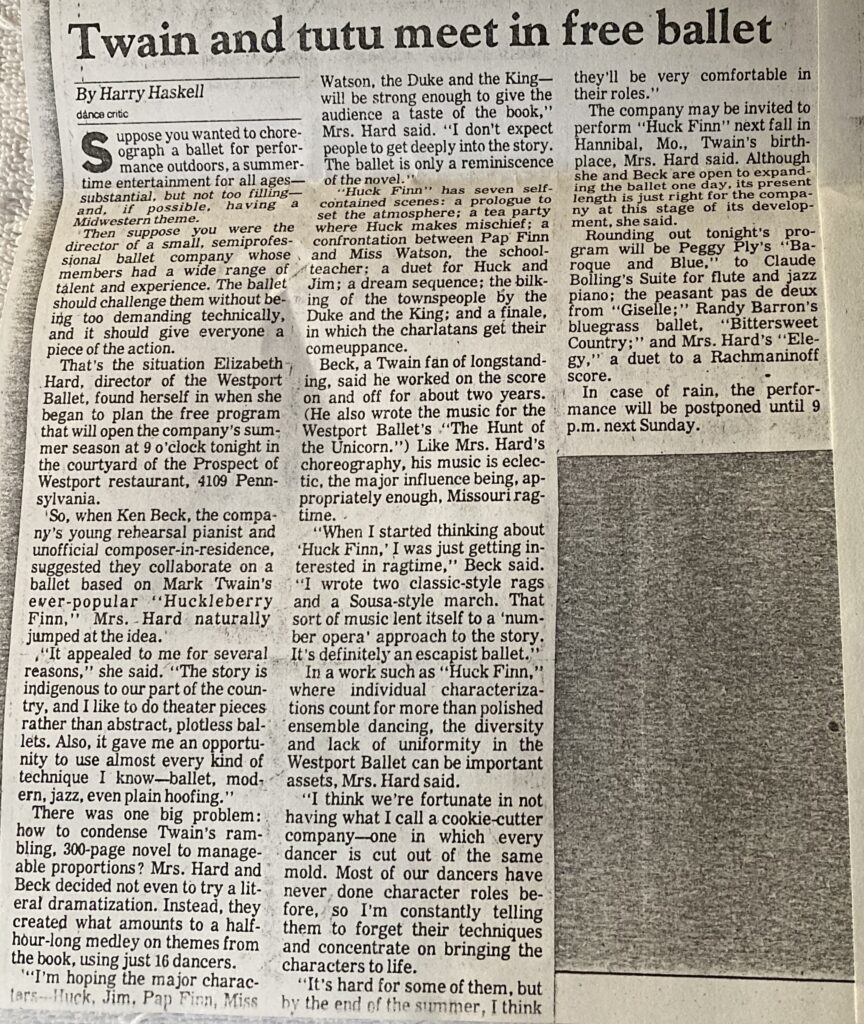

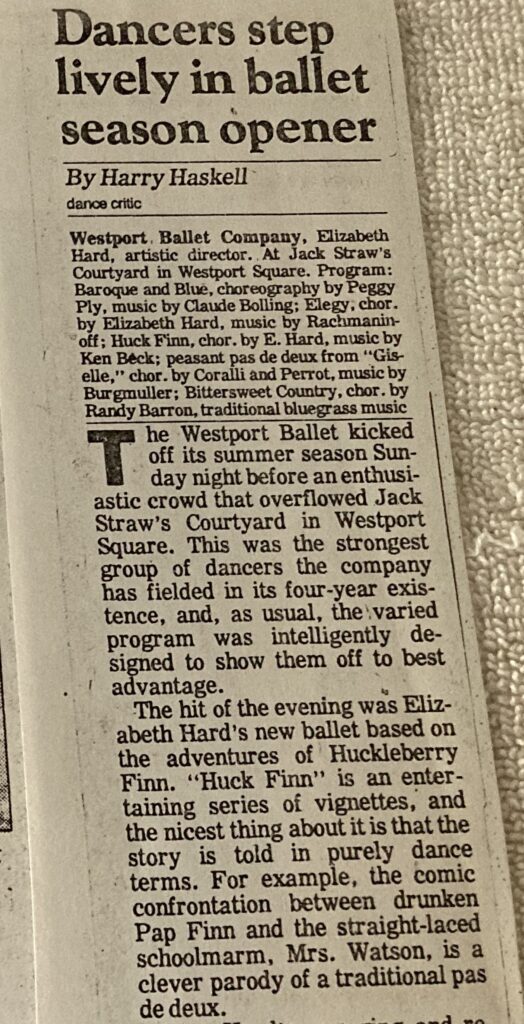

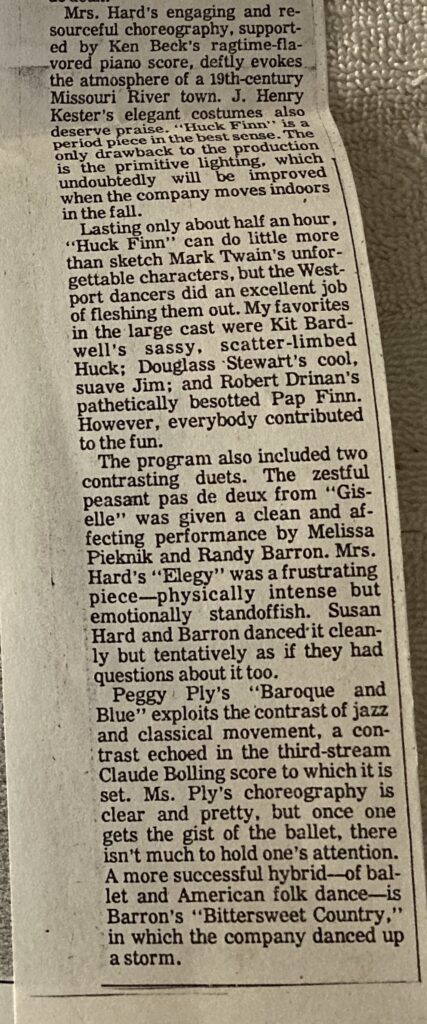

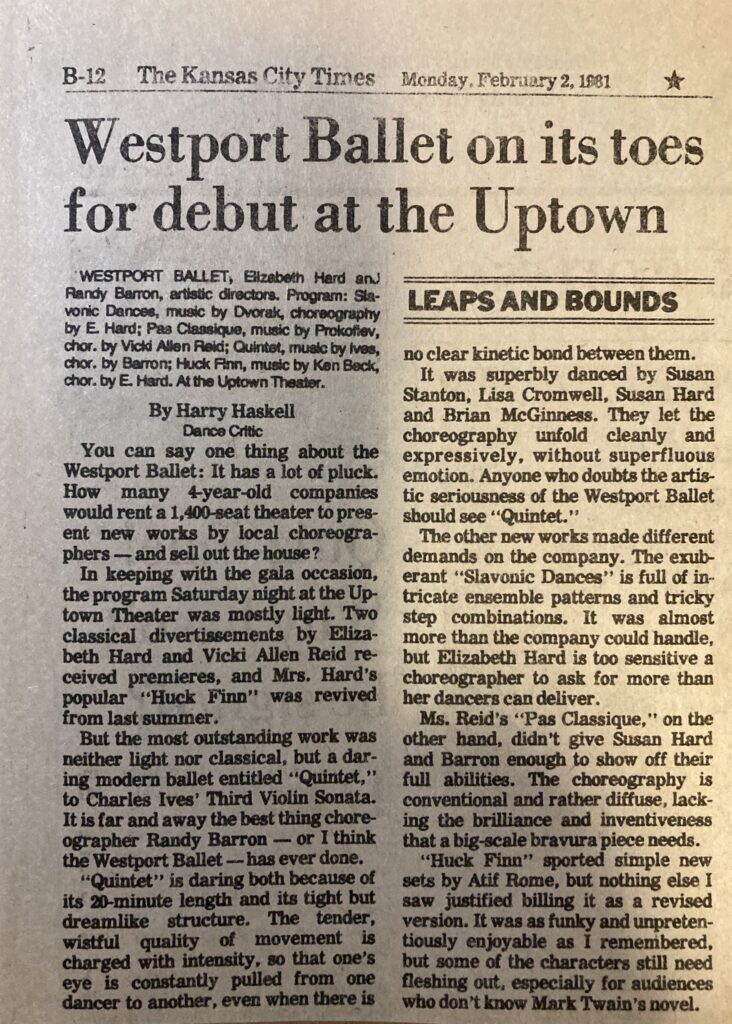

I also remember talking to Harry Haskell, the KC Times music and dance critic, for the article. This and his review are posted in part above. At the conclusion, I’ll post them both complete.

The Jack Straws performances were given more than once. I must’ve (should have) gone to all of them. I might have been running sound. That would account for why the whole series is a bit of a blur. I know my parents came out to see the show in the courtyard. It was a moment of triumph, no denying it.

Planning for taking the company, and Huck, indoors to a proscenium stage evolved rapidly. In the event, the billing of an expanded version of Huck exceeded my ability to pull it off. The venue was to be the Uptown Theater. There was an undertow eating away at available time and concentration in the wake of the Jack Straws performances. Phil DeWalt knocked on the door at 301 E 43rd St., packing a pile of his scores. Phil brought along a few others, and introduced me to still more. Micheal Redden, the piano tuner, who in amazing stroke of irony had also been in Sioux City at Western Iowa Tech getting training in piano repair, was a forceful personality and wildly entertaining. Dwight Frizzell appeared around this time, and I went to his gigs in various places. Pat Ireland, the fiddler and electric violinist, was soon in the mix. I was awash in riches, but very, very distracted. Phil had introduced me to C. V. Alkan, yet another dead white guy piano player/composer. Hair raising difficulty and virtuosity was the challenge thrown down by this man and his music. I also wanted to consider getting at the heart and soul of the Twain novel. The heart of Twain’s novel, it seemed to me, was the moral imperative embodied in the character of Jim, the runaway slave. The character is complex, and the complexity expands as the novel progresses. He sees through pretense; he is rooted in ‘common sense.’ He puts the white folks to shame. My little soft shoe ragtime piece, with its restless modulations and relentless triplets were not floating my raft. Jim is also superstitious. The mix of common sense and superstition became the focus of Night on the River. Listening now, I can still close my eyes and imagine the softly told tales told on the sandy river bank of ghosts and premonitions. From Jim’s mouth into Huck’s boyhood imagination the lore flows, about half as fast as a man can walk; the pace of the relentless river. Plus, the piece is slow paced, and not that hard to read down.

The opposite was true of the Funeral March. Into the scene where the ‘King’ and the ‘Duke‘ are attempting to impersonate the brothers of the late Peter Wilks, are exposed as grifters, and ultimately tarred and feathered, I poured all I had learned so far. I mean that musically as much as in any other way, but I was also cranking it up a notch emotionally. Musically, I was being my usual snarky, in-jokey self, in that I was poking fun at period ‘battle music,’ with its tremolos and other hokey effects. This is not farfetched in the least; here’s a passage at the beginning of Walter Harding’s Bibliography of Thoreau in Music (1992), that sums up what I had already known by 1980:

“He (Thoreau) loved romantic ballads such as “Tom Bow- line” and the “Canadian Boat Song” and reveled in that atrocious warhorse “The Battle of Prague” that brought such joy also to Huckleberry Finn when it was played for him by one of the Grangerford girls.”

For more on Frantizek Kotzwara and the Battle of Prague, follow the links.

Digression into battle music, and specifically The Battle of Prague:

An interesting graphic representation. An orchestral performance.

The score is available at IMSLP.

Somebody else’s snark on the topic.

I was also employing effects that came from Henry Cowell and friends: the forearm clusters, the silent depressing and holding of a chord, the release of the damper pedal, and the resulting ghost chord ringing until the keys are released. Eubie Blake’s broken octaves and tenths. Alkans octaves. Fats Wallers tenths. Even a bit of aleatory. The net result: I had made a piece I couldn’t for the life of me play. I tried. I had thought while going for broke in the writing, that maybe I’d grow into it. I’d force myself to master it. But I ran out of time.

When the pieces were recorded by Tom Mardikes at the UMKC’s White Recital Hall, me playing a wonderful Bösendorfer grand, the clock was running, the company was paying, I was trying to limit numbers of takes, and I just ran out of time and energy. I had to go back to Liz and tell her I was not going to come up with any more scenes beyond Night on the River. And so the performance happened. The review, again by Haskell, more or less highlighted my failure to deliver more. See below.

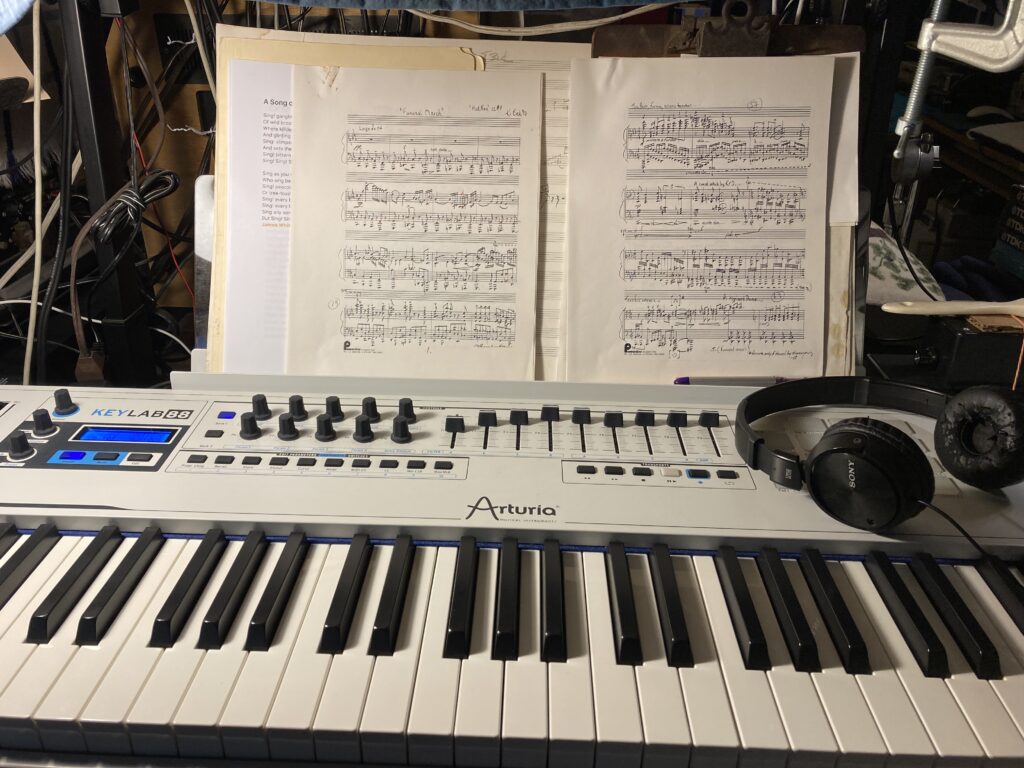

Flash forward to last week, April of 2023. I fished out the Scene 7 score, determined now to realize the missing material. It was to have preceded the Final March. It might have ‘fleshed out’ the ballet, though it would certainly have challenged Liz and the company as much as it challenged me. Now, I wanted, at least, to hear it ‘played.’ Now I have the tools to do it. I used Logic Pro, and an Arturia Keylab 88. I did not feel any compunction to play real time. I played in as much as possible, since that’s easier than step entry or (worse) entry of notes by hand-to-mouse. I was careful to map the tempi properly and credibly, and I carefully tailored the dynamics (velocity editing). Here are some photos of the set-up during the process:

Above: I played the score in on this keyboard.

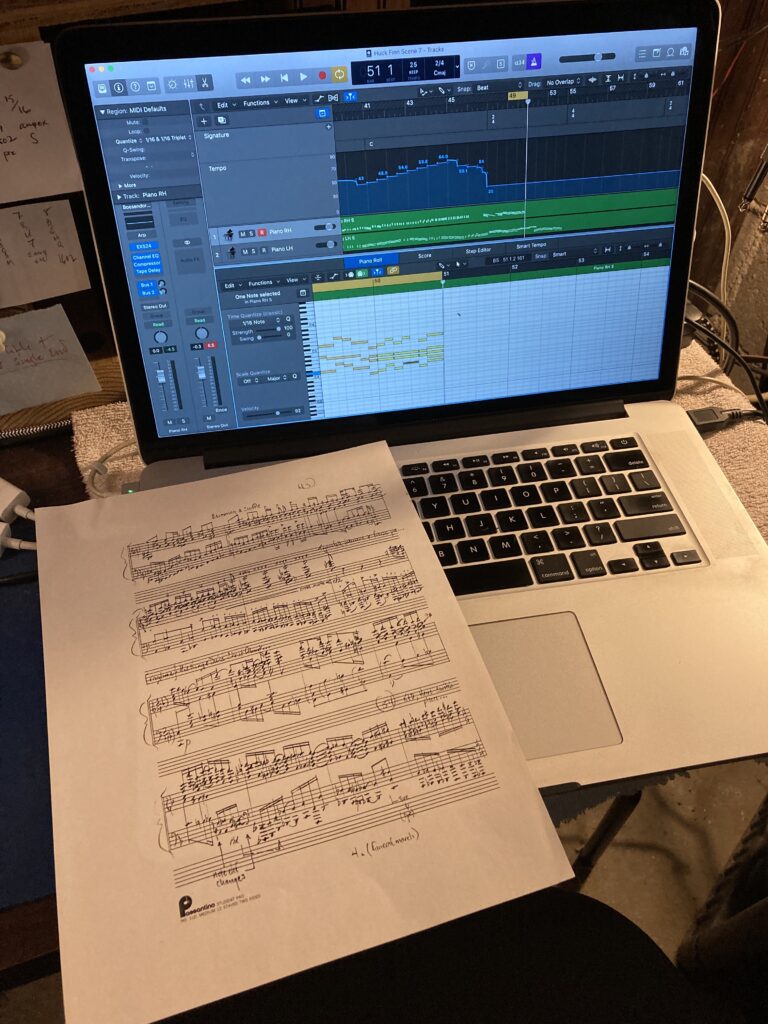

Editing in progress…

MIDI editing on Logic Pro (or any other similar workstation) gives one absolute control over every aspect of a usually keyboard-oriented performance, separate from the sound. The digital data (the ‘d’ in MIDI) is then routed, either internally (most convenient usually), or externally to the sound maker of ones choice. I used a sound in Logic that imitated the Bösendorfer piano. It is all too easy to get hung up in details using this system. As you can see above, where the blue line represents the tempo map, I’ve dropped back to a very slow tempo for recording. I also have a metronome going on each beat, and each subdivision. And then, in editing, timing is quantized to a grid that is suitable for the passage in hand. Logic features a few editing modes. The photo shows the so-called piano roll mode. But there is also a score editor, which is more convenient for certain types of edits. (Ex: Did I actually get that pitch right?)

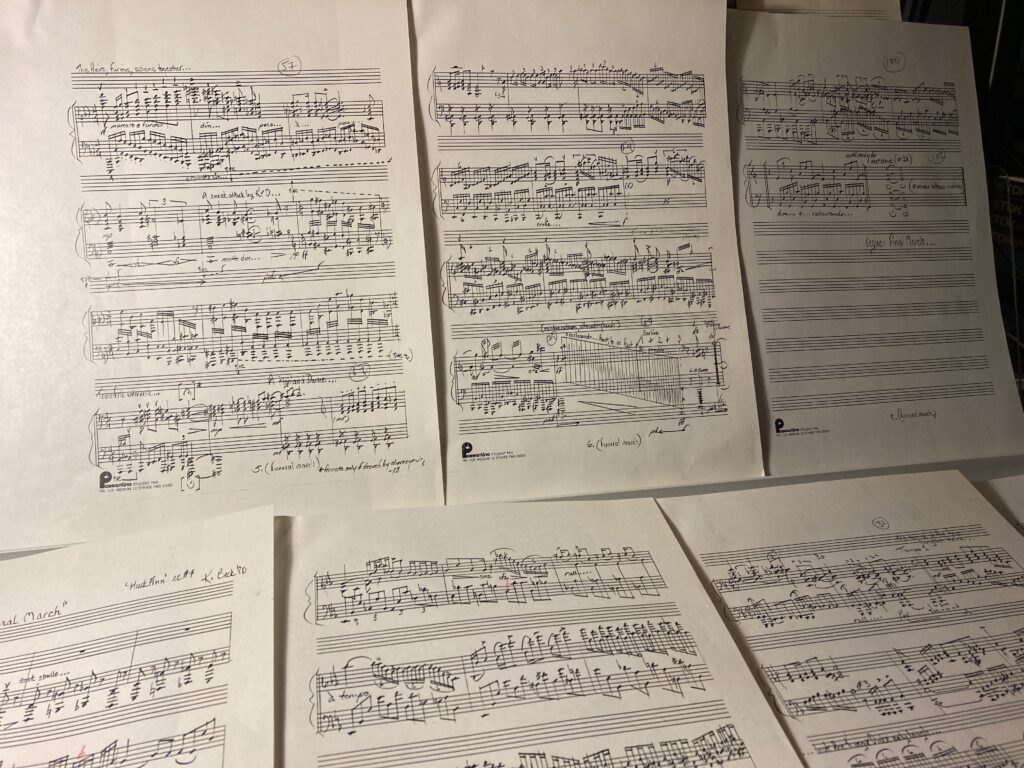

Above: the score, spread out for a last check. It’s a xerox copy of my pencil manuscript, so I felt free to mark it up. I also felt free to make changes to where meters shifted. The piece zig-zags between simple and compound meters, with tuplets and duplets occurring no matter what the basic meter.

Below: the clippings from the Kansas City Times newspaper…

KC Times, June 15th, 1980

KC Times, June 16th, 1980…

I played some of these pieces for years in dance classes. The rags and the march past is for the most part square, ie., 8 or 16 bar phrases. The Prelude doesn’t work as well in classes without modification. And as for the ill-fated scene 7, if I wanted to play difficult music for dance classes, I could always read the Goldberg Variations. Eventually, I tired of the pieces as repertory, and forgot about them. I never forgot the project, of course. I lament to this day that this might have been my high water mark as a composer/performer. And so it is good to get these out, dust them off, and let them languish afresh on the internet.

And… as an epilogue to the epilogue… here’s a review of possibly the last ever time the ballet was done. I was within days of saying goodbye to Kansas City when this went up at the courtyard. It was part of the same summer series that it premiered at, so it went on there without me. Nowadays, the thought that that happened brings a dash of delight to my old cynical bones.